Main Areas of Interest

Throughout my entire professional career, I have made the treatment of diseases of the spinal cord and the head and neck junction my main area of work.

During this period, I advised and cared for over 5,000 affected patients and personally operated on around 1,500. In each individual case, the recommendation for surgery was the result of detailed discussions and examinations of the patient. The opportunities and risks of surgical treatment were carefully weighed up and compared with the risks that would be taken if surgery was not carried out.

For each individual patient, what further treatment should look like after the operation is explained in advance. It never ends with the application of the wound dressing at the end of the operation but often includes subsequent rehabilitative therapy in a suitable center. This is discussed before the operation and then finalized with the patient in the first few days after an operation. Even after that, my care for the patients continues.

Outpatient follow-up examinations with current magnetic resonance images 3 months after the procedure have proven particularly useful. The surgical area will then usually have healed and you can discuss what further therapy should look like.

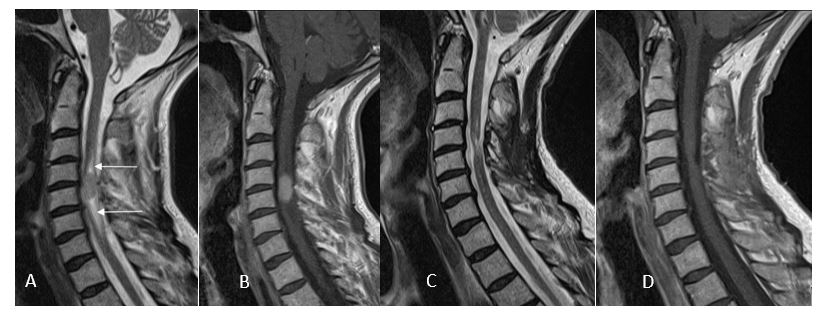

Tumors located inside the spinal cord (so-called intramedullary tumors) have to be distinguished from those arising outside with compression of the cord from outside (so-called extramedullary tumors). Statistically, about 95% of these tumors are benign and grow very slowly. Consequently, radiotherapy or chemotherapy are no advisable treatment options in general, as these modalities tend to be ineffective in the long term. The treatment of choice is surgical removal, which should be undertaken early, before serious disabilities have already set in. This principle applies to intramedullary tumors in particular. Modern magnetic resonance imaging devices now provide high-resolution images of the spinal cord, which allow precise surgical planning.

(A) Intramedullary tumor at C4-C5 level with small cysts above and below (arrows) and homogeneous contrast enhancement (B). 3 months after complete removal of the tumor (ependyoma), no residual tumor visible (C, D) with normal mobility and use of both arms and hands.

Thus, surgical dissections can minimize the risks for permanent damage of nerves or spinal cord tissue. The aim of surgery is a complete tumor removal with preservation of neurological functions. For patients undergoing tumor surgery for the first time, a complete tumor removal could be achieved in more than 85% of patients with intramedullary and in more than 90% with extramedullary tumors. In such cases, the tumor does not reappear later in life. For the remaining patients, a decision must be made on a case-by-case basis as to whether and when another surgical intervention should be performed once a residual tumor grows again or recurs.

(A) Extramedullary tumor in front of the spinal cord at the level of Th2 – Th3 with homogeneous contrast uptake (B). 3 months after complete tumor removal (meningioma) no recognizable residual tumor (C, D) with complete neurological recovery

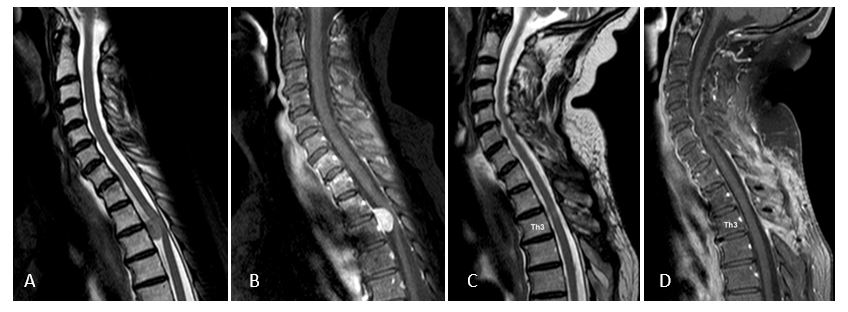

Often spinal cord malformations are associated with with bony malformations of the spine. Two mechanisms may interfere with spinal cord functions in these patients: fixation of the spinal cord (so-called tethered cord) – either by a thickened filum terminale below the so-called conus, by attachments to spinal meninges, or by bony spurs and aberrant soft tissues penetrating the spinal cord dividing it into two parts (so-called split cord malformations or diastematomyelia). Any fixation of the spinal cord may lower spinal cord blood flow or lead to overstretching of nerves with particular body movements. Alternatively, the spinal cord may be compressed due to narrowing of the spinal canal by concomitant bony malformations or degenerative changes or due to so-called dysraphic tumors (lipomas, dermoids, epidermoids, glioependymal and neurenteric cysts). Therefore, each individual patient must be analyzed carefully for signs of fixation or compression of the spinal cord, which may also occur in combination, in order to determine the correct treatment strategy. Early intervention with the right strategy is crucial for a good long-term outcome, particularly if spinal cord malformations become symptomatic in adulthood. If no previous operations have been performed and depending on the complexity of the malformation, surgery can stop further neurological progression long-term in 70-90% of adult patients.

Fixation and splitting of the spinal cord (split cord malformation type I) by a bony spur at the level of L1 (A, B). 3 months after surgery with removal of the spur and reconstruction of the dura (C, D) with preservation of all neurological functions

(A) Intra- and extramedullary dermoid cyst at the level of Th12. 1 year after complete cyst removal, no signs of recurrence (B), improvement of pain and preservation of mobility, bladder and bowel control

The term syringomyelia describes a cyst formation within the spinal cord. However, not every cystic change in the spinal cord should be called syringomyelia. Most importantly, a widening of the so-called central canal inside the spinal cord is often misdiagnosed as syringomyelia in magnetic resonance imaging. It represents no spinal cord abnormality and should be interpreted as a slight anatomical variation of no clinical significance as it never causes or explains any symptoms.

Numerous studies over the last 40 years have shown that syringomyelia is not a spinal cord disease in its own right but always caused by another disorder. In other words, the underlying disease triggering syringomyelia must be identified in each patient. Once the underlying disease is treated successfully, syringomyelia will regress.

Syringomyelia is most commonly caused by disorders leading to obstructions of cerbrospinal fluid (CSF) flow around or along the spinal cord. Other possible triggers are tumors in the spinal cord or spinal cord malformations. In about 90% of patients with syringomyelia, treatment of the underlying cause can be offered. However, this requires an exact diagnosis and precise planning of the intervention, so that the syringomyelia may regress subsequently.

Irrespective of the cause of syringomyelia, the postoperative results showed that the symptoms related to the underlying disease respond best to surgery, while symptoms attributable to syringomyelia improved less well. Unfortunately, this applies in particular to neuropathic pain, which improved in a third of patients only. Therefore, it is most important to plan surgery before severe symptoms ot syringomyelia such as neuropathic pain syndromes have appeared.

(A) Syringomyelia from C4 to Th8 due to arachnopathy compressing the spinal cord from behind at Th8/9. (B) 4 months after removal of the arachnopathy, the syringomyelia disappeared completely with preservation of neurological functions and improvement of paraesthesias

Diseases of the so-called arachnoid have to be distinguished from those of the so-called dura. Diseases of the arachnoid, i.e. arachnopathies, may lead to fixation of the spinal cord to the dura, to disorders of spinal cord blood flow, to obstructions of CSF-flow resulting in syringomyelia and to compression of the spinal cord once pouches or arachnoid cysts have formed. For most arachnopathies, the cause cannot be identifed and a congenital alteration of the arachnoid is therefore assumed. In about 30% of patients, however, the cause of the arachnopathy is known, such as spinal injuries, surgical interventions on the spinal cord or long-term complications of meningitis or spinal hemorrhages (subarachnoid hemorrhage). With few exceptions, arachnopathies tend to affect the area of the thoracic spine only. Not all arachnopathies lead to symptoms and require surgical treatment. In general, an operation is recommended for symptomatic patients only, as the prevention of further neurological progression can by achieved with surgery in most instances only. Unfortunately, arachnopathies as a result of previous operations, inflammations or hemorrhages do not respond favourably to surgery.

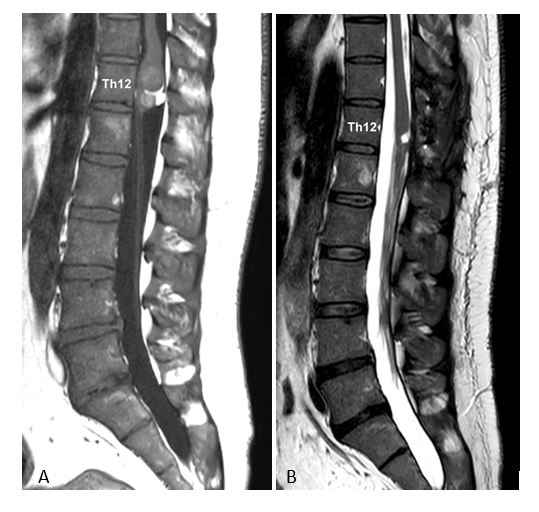

Diseases of the dura may develop as a result of injury or surgery or may occur spontaneously. Some rare, genetic disorders can also lead to changes of the dura. The commonest disorders of the spinal dura are so-called diverticula, i.e. circumscribed, cyst-like protrusions of the dura, which may remain asymptomatic for a very long time despite changing the surrounding bone over the years. Depending on their size, irritation and compression of individual nerves or the spinal cord may develop. As long as they remain asymptomatic, these diverticula do not require surgery.

(A) Diverticula of the dura mater from L1 to L5 with severe compression of spinal nerve roots (B). The cause was a defect in the dura at the level of L5 on the left side. (C) 3 months after exposure at the level of L5 only with closure of this defect, the patient is symptom-free with complete resolution of the diverticulum.

The most common disorders in this region are Chiari malformations. Originally described by Hans Chiari at the end of the 19th century as brain malformations and classified in 4 types, we now know that these malformations are the result of a mismatch between the size of the skull and the size of the brain. Types I and II are of particular clinical importance. Depending on the bony anatomy, parts of the cerebellum, which is located in the occipital area, or the so-called brainstem may be forced to move down into the upper spinal canal. As a result, these herniated parts may exert pressure on the spinal cord. Additionally, CSF-flow between skull and spinal canal may be obstructed.

Compression of the spinal cord and CSF-flow obstruction may lead to a variety of complaints:

- Occipital headache triggered by coughing, sneezing, laughing, or straining

- Coordination disorders, especially in lower limbs resulting in unsteady gait

- Disorders of sensation

- Swallowing problems due to compression of nerves controlling swallowing

- Sleep apnea syndromes

- Spinal misalignments, i.e. scoliosis

The clinical picture varies depending on the type of malformation, the age of the patient and presence or absence of concomitant malformations of the joints at the craniocervical junction. In the first 2-3 years of life, Chiari malformations may lead to life-threatening disorders of breathing, circulatory control and swallowing functions requiring urgent decompressions. Such dramatic situations no longer arise after the age of three. In symptomatic children at school age for example, scoliosis and coordination disorders are observed, especially at the time of body growth during puberty.

In adult patients on the other hand, occipital headache represent the commonest symptom affecting about 80% of them. In children, the typical occipital headache asssociated with Chiari is rather the exception and not a regular feature.

Due to these various aspects, it must therefore be checked in each individual patient whether surgical treatment is necessary and what it should incorparate.

Chiari I represents the commonest malformation at the craniocervical junction describing a constellation in which the occipital foramen – the so-called foramen magnum – is of normal size, while the size of the posterior part of the skull is slightly reduced forcing the so-called cerebellar tonsils to move into the spinal canal.

The associated obstruction of CSF-flow may lead to cyst formation inside the spinal cord, i.e. syringomyelia. The incidence of syringomyelia in Chiari I increases with age, affecting approximately 50% of children and 75% of adults. That a Chiari I malformation blocks CSF-flow to such an extent that hydrocephalus results is a rare observation in less than 1% of patients.

Treatment of choice for a Chiari I malformation is the so-called decompression of the foramen magnum. Bony parts of occipital bone and first cervical lamina are removed followed by opening the underlying dura for a so-called duraplasty to provide sufficient space for cerebellum, spinal cord and CSF-flow.

American pediatric neurosurgeons in particular recommend to restrict surgery to a bony decompression without duraplasty. While this strategy may avoid rare complications related to dura opening and suturing, it has been shown in a number of studies, that postoperative long-term results are poorer and rates for regression of syringomyelia lower with this strategy. Therefore, I do not offer decompressions without duraplasty for Chiari patients.

(A) Chiari I malformation with large syringomyelia extending into the thoracic spine. (B) 3 months after decompression of the foramen magnum with duraplasty, the occipital headache has disappeared and the syringomyelia has clearly regressed

In about 10-15% of patients with a Chiari I malformation, there are concomitant malformations of craniocervical joints and skull base, which are summarized under the term „basilar invagination“. This refers to the anatomical constellation of an abnormally high positioned part of the second cervical vertebra – the so-called dens. There are several possible causes for this abnormal position of the dens:

- Bony malformations of the skull base

- Absent joints between skull and first vertebra

- Instability between the first and second cervical vertebra.

Depending on the anatomical constellation overall, it must be analyzed individually, whether additional fixation between the first and second cervical vertebra (C1/C2) is required if a decompression of the Chiari I malformation is planned in a patient with concomitant basilar invagination.

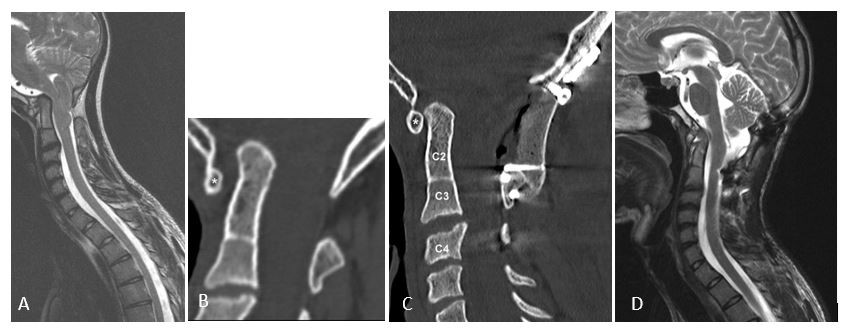

(A) Chiari I malformation with basilar invagination, luxation between C1 (star) and C2 with absent joints between skull and C1 and C2 and C3 (B). 3 months after realignment and fixation of C1/C2 and foramen magnum decompression (C), the spinal cord is completely decompressed (D) with improved hand functions and mobility

This malformation is significantly rarer than the Chiari I malformation and almost exclusively affects patients with spina bifida. The Chiari II malformation is not an advanced form of the Chiari I malformation, but a fundamentally different clinical disorder. While the skull is too small for the brain as in Chiari I, this mismatch is already present before birth and so profound, that the foramen magnum and upper spinal canal are widened. The obstruction of CSF-flow is so pronounced, that almost all children develop hydrocephalus in infancy after closure of the spina bifida, which then has to be drained with a so-called shunt. This shunt also relieves the pressure at the craniocervical junction so that symptoms of a Chiari malformation as mentioned above usually do not longer develop.Therefore, just a minority of patients with a Chiari II malformation with functioning drainage of the hydrocephalus require additional decompression later in life. If this is necessary, decompression is not performed at the foramen magnum as in Chiari I, but in the upper cervical spine to that extent as the cerebellar tonsils are displaced.

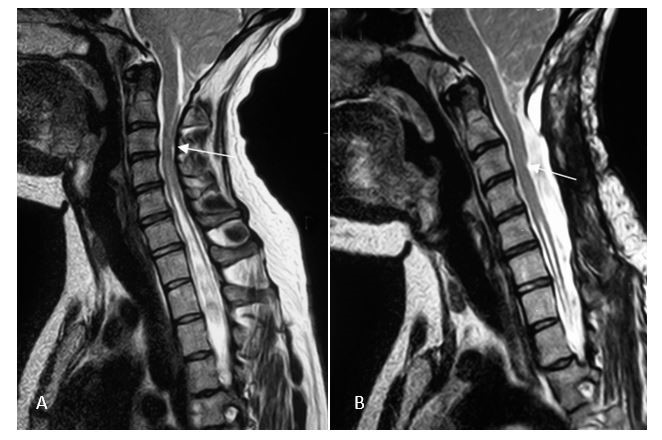

(A) Chiari II malformation with large syringomyelia in a young woman. The cerebellar tonsils extend to C3 (arrow). 3 months after decompression with stabilization of the cervical spine and enlargement of the dura, the syringomyelia has regressed (B) with improved motor skills in her hands

With the right indication, i.e. timely surgery and right strategy, patients with a Chiari I malformation can lead a completely normal life.

Experience has shown that patients with basilar invagination are affected more seriously compared to those with Chiari I only. Even after successful surgery, they usually remain physically restricted as they were before surgery. The same applies to patients whose accompanying syringomyelia has already become symptomatic before surgery. Decompression of a Chiari II malformation can be life-saving in selected cases in infancy. In older children or adults, decompressions may stop further progression of the disease.